Hydrothermal Alteration 101

Definition: The crustal fluids that form ore deposits, are commonly out of chemical equilibrium with the rocks they pass through. This leads to reactions between the fluid and the rock, causing some minerals in the rock to be replaced by new minerals, and the rock is then altered. The new minerals are called alteration minerals and the pathway through which the fluid moved forming the alteration minerals is called an alteration zone. Alteration zones may form below the mineral deposit (commonly called footwall alteration) as the fluid moves toward the site of mineral deposition or above and surrounding the deposit (called hanging wall alteration). as the “spent fluid” moves through the rocks away from the deposit. As the fluid reacts with the rock and forms alteration minerals, the fluid itself changes in chemistry such that further along its path it has changed so much that a different alteration mineral is formed. This progressive change in alteration minerals away from or towards a deposit is called alteration zonation. Other factors such as changes in rock composition or fluid temperature or pressure or fluid/rock ratio may also cause alteration zonation.

Why study mineral alteration and zonation?

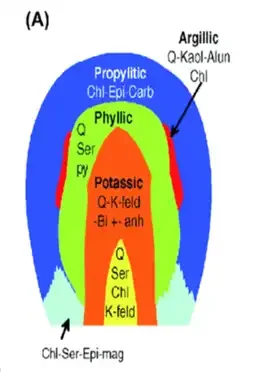

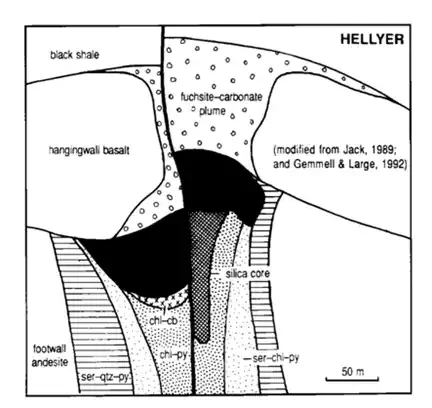

Progressive changes in alteration mineralogy leading to zonation can give information about where a sample exists in space with respect to an orbody. By studying several similar deposits a model of alteration zonation can be developed, as is the case in the Howel and Guilbert (1970) alteration model for porphyry copper deposits or the Gemmell and Large (1992) model for VHMS deposits. In the first case, if your drill intersected intense K-feldspar alteration you know from the H & G model that you are in the core and close to Cu mineralisation. On the other had if the drill intersected quartz-muscovite-pyrite you are probably in the outer phyllic alteration zone, and you need to drill deeper.

Classic Models of alteration zonation

Two classic alteration models (A) Porphyry copper deposits based on the SW USA deposits (Lowell and Guilbert, 1970) and VHMS deposits based on Hellyer, Tasmania, but incorporating features from Canadian and Japanese deposits (Gemmell and large, 1992)

Several models of hydrothermal alteration around porphyry copper deposits have been developed over the past 50 years. The initial models, based on the south-west USA porphyries (Lowell and Gilbert, 1970; Fig 1A), showed concentric zoning around the central productive porphyry of potassic alteration (K-feldspar, biotite) in the core followed by phyllic (sericite-pyrite) alteration merging outwards to propylitic (chlorite, epidote, albite) alteration at the periphery (Fig. 1A). The model showed a Cu shell overlapping the boundary between the potassic core and phyllic envelope.

Early alteration models for VHMS have progressed from Sangster (1972), Large (1977), Franklin et al (1981) to Gemmel and large (1992), however all with similar elements of an intensely altered footwall pipe zone to weak diffuse hangingwall alteration. The pipe shown here is zoned with a silica-rich core followed by strong chlorite-pyrite alteration, then a zone of sericite-pyrite-chlorite and outermost zone of quartz-sericite-pyrite which merges with the footwall volcanics.

Intensity and pervasive vs fracture-controlled alteration

The intensity of alteration is commonly controlled by the water-rock ratio and permeability of the rock. Pervasive alteration where the whole rock is effected due to high water-rock ratios and high permeabilty is common in the inner footwall pipe zones of VHMS, whereas the spent hanging wall fluids are less intense with resultant fracture controlled and phenocryst controlled alteration. Porphyry copper alteration is commonly vein-fracture controlled. In the core of the porphyry deposit high fluid pressures mean that the intensity of veining and alteration commonly results in the rock being both veined and pervasively altered, but towards the outer alteration zones the fluid pressure, veining and intensity of alteration is considerably less and relatively unaltered rock can persist between the veins and their alteration halos (Cathles and Shanon, 2007).