Fundamentals

The crustal fluids that form ore deposits, are commonly out of chemical equilibrium with the rocks they pass through. This leads to reactions between the fluid and the rock, causing some minerals in the rock to be replaced by new minerals, and the rock is then altered.

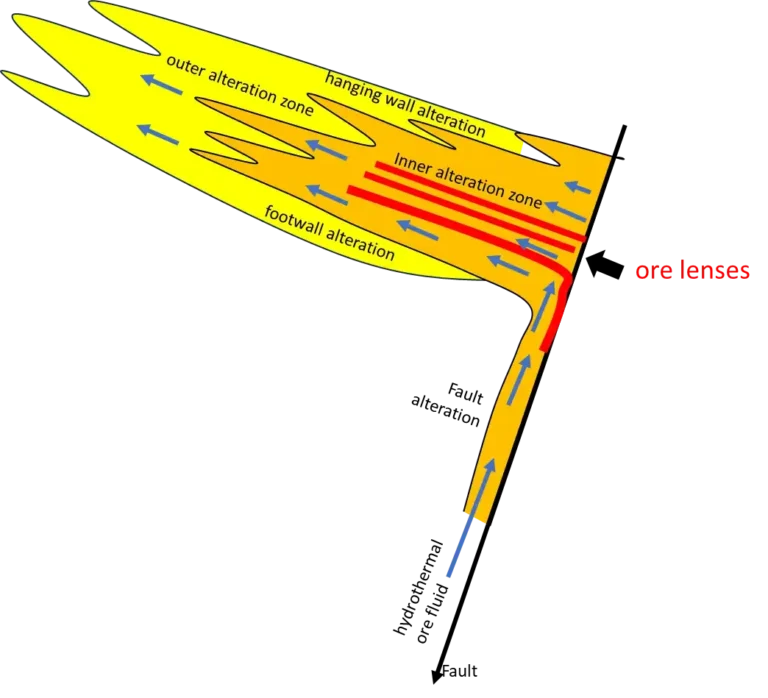

The new minerals are called alteration minerals and the pathway through which the fluid moved forming the alteration minerals is called an alteration zone. Alteration zones may form below the mineral deposit (commonly called footwall alteration) as the fluid moves toward the site of mineral deposition or above and surrounding the deposit (called hanging wall alteration).

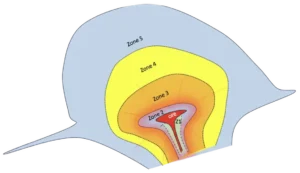

As the “spent fluid” moves through the rocks away from the deposit, it reacts with the rock and forms alteration minerals, the fluid itself changes in chemistry such that further along its path it has changed so much that a different alteration mineral is formed. This progressive change in alteration minerals away from or towards a deposit is called alteration zonation.

Other factors such as changes in rock composition or fluid temperature or fluid mixing or pressure or fluid/rock ratio may also contribute to alteration zonation.

Progressive changes in alteration mineralogy leading to zonation can give information about where a sample exists in space with respect to an ore body.

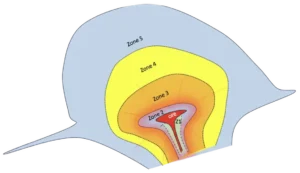

By studying several similar deposits a model of alteration zonation can be developed, as is the case in the Lowell and Guilbert (1970) alteration model for porphyry copper deposits or the Gemmell and Large (1992) model for VHMS deposits.

In the first case (A), if your drill intersected intense K-feldspar alteration you know from the L & G model that you are in the core and close to Cu mineralisation. On the other had if the drill intersected quartz-muscovite-pyrite you are probably in the outer phyllic alteration zone, and you may need to drill deeper.

In case (B) if the drill intersects intense chlorite alteration you may be below the massive sulfide. But if it intersects weak carbonate-fuchsite you need to drill deeper.

An alteration vector is some aspect of alteration that changes in a defined way as you approach an ore deposit. It may be one of the following;

This website concentrates on alteration vectors derived from whole rock chemistry (second dot point)

One of the oldest whole-rock alteration vectors, designed to help find japanese VHMS ores (Kuroko deposits), is the Ishikarwa Alteration Index (AI);

AI = 100* (K20 + MgO)/(K20 +MgO+ Na2O + CaO).

This index varies from 30-40 for least altered volcanics to 90-100 for intensely altered volcanics commonly adjacent to the ore deposit. It was designed by Ishikarwa (date) to measure the breakdown of plagioclase phenocrysts and groundmass glass (Na2O + CaO loss) and their replacement by white-mica and chlorite during alteration (K2O+MgO gain) by the ore-forming fluids. Many other alteration vectors use this principle of ratioing (elements lost during alteration)/(elements lost + elements gained)

Intensity of alteration is basically a semi quantitative measure of what percentage of the rock is replaced by new alteration minerals. It may be designated weak, moderate, strong or intense by visual logging.

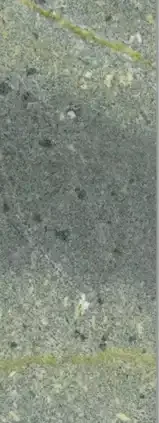

In VHMS alteration for example, the volcanic rock is commonly pervasively altered; weak alteration my be due to partial rerplacement of feldspar phenocrysts by sericite and carbonate, moderate alteration may be complete replacement of all phenocrysts both felsic and mafic. Strong alteration involves all phenocryst and partial ground mass replacement and intense alteration is when all volcanic textures are destroyed and all primary minerals have been replaced by new minerals.

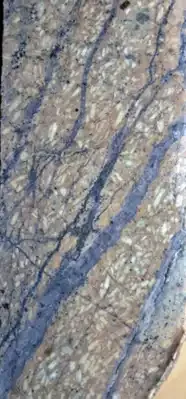

The alteration process in porphyry Cu-Au deposits commonly involves fracture based alteration rather than pervasive alteration, although both process may be present as the intensity of alteration increases. The most intensely altered zones in PCD show abundant generations of veining with the percentage of quartz veining overprinting other alteration phases being a key vector to ore.